India Now! Retrospective

Toronto International Film Festival Program Guide

1994

English, August

Centuries ago, the proxy for one of India’s earthly conquerors watched a caravan of elephants laden with gold, precious gems and sumptuous cloth wend its way west. He wrote to his master: “Sire, this land is rich beyond the dreams of avarice.”

Today, India is no longer the place of enigma and mystery this tale conjures up—after all, people of Indian descent make up an essential part of our community—but the great wealth, now per- haps more cultural than mineral, it alludes to has never been more certain.

Literally hundreds of films are produced and released every year in India. They are made in a variety of languages, so that some films are seen only in the area where a particular language is spoken. Others, the most popular, are dubbed. Others still—the “uncommercial, art” films—are seen within the rather narrow confines of festivals and cultural centres. And, while it is tempting to remember Kapoor, Ray and that fabulous trove of mythologicals and musicals, we have disciplined ourselves, opting instead for a portrait of Indian cinema now. We decided, of course, to choose the very best films we could find and now immodestly believe that the programme gives a very clear idea of what is happening in Indian film today.

One of the absolute requisites in our minds was to include popular films, which have been undeservedly dismissed by so many. The self-styled Indian “cultural elite” has long refused to take these films seriously, even as they praised American and European art cinema. Yet popular musicals contain more energy, more vital creativity, and, oddly, allow more freedom of the creative imagination than the most “artistic” of the cinéma d’auteur. These films are long and include everything—romance, adventure, tragedy, comedy, and always those hallucinatory songs and dances, which are sometimes used to further the plot and just as often simply there to delight. There may be no message (thank God!), but they move, they entertain, and they are finally why we all fell in love with movies in the first place. Mani Rathnam—several of whose films appear in a special section—is, to our minds, the master of the modern popular musical. If his magical films don’t delight you, perhaps you are beyond delight.

When Satyajit Ray’s classic Pathar Panchali screened at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, it revealed an India rarely seen before and demonstrated the possibilities of another kind of cinema. India’s rich tradition of art cinema has flourished ever since, often drawing—like the popular films—on music and dance for their inspiration. A good deal of this programme is made up of “serious” films which tell Indian stories about ordinary people living their lives. Often based on literary sources rarely circulated here, the films are set in the villages and in the cities. They remain basically and authentically Indian, but touch universal themes found in important world cinema.

After independence, documentary film in India was dominated by Films Division, the Indian equivalent of the National Film Board of Canada. Long compromised by real and imagined “third-world aesthetics” and political interference, Films Division has gradually lost its influence. But it is only over the last few years that young directors, with diverse backgrounds and varying agendas, have created a truly independent documentary scene. Some have examined the cultural past—many seem fascinated by the working of the cinema itself—and others have looked with a none-too-kindly eye at politics and society.

So, then, here is India now as mirrored in thousands of images created by the finest film artists now working. Here is the proof that India is indeed a land of riches beyond the dreams of avarice.

—David Overbey & Noah Cowan

This programme would have been impossible without the support of several people. In Toronto, Dr. Atul Tolia has done outstanding work promoting this Festival corporately and within the community. In India, we received essential assistance from Ms. Uma da Cunha, Mr. S. Narayanan of the National Film Development Corporation, Ms. Malti Sahai and Mr. Sunit Tandon of the Directorate of Film Festivals and Ms, Riva Vaidya and Mr. Riyad Wadia and their families. Thank you.

Bandit Queen

OPENING NIGHT

Bandit Queen

Shekhar Kapur

INDIA, 1994

119 minutes Colour/35mm (Hindi)

Production Company: Film Four International/Kaleidoscope

Producer: Sundeep S. Bedi

Screenplay: Mala Sen

Cinematography: Ashok Mehta

Editor: Renu Saluja

Art Director: Ashok Bhagat

Sound: Robert Taylor, Tom Lewiston

Music: Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

Principal Cast: Seema Biswas, Nirmal Pandey, Manoj Bajpai, Rajesh Vivek, Raghuvir Yadav, Govind Namdeo, Saurabh Shukla

Phoolan Devi, India’s most famous outlaw, is still a controversial figure. Named Goddess of Flowers, the Bandit Queen was accused of murder and kidnapping, including slaughtering 30 men in a raid dubbed the Behmai Massacre, an event that brought down an entire government. When she surrendered in 1983, it was on her own terms, before a crowd of 10,000 cheering fans, who thought of her as an avenging angel, the scourge of the rich and protector of the common man.

Shekar Kapur’s film is based partly on her autobiography, a version of her life that she has now disowned. Seeking to read behind her words, Kapur and writer Mala Sen have tried to see where she was overly self-serving or under romantic illusion (as with her treatment of her lover). The filmmakers are sympathetic, however, and never attempt to mitigate the circumstances which drove Devi to violence. The screen re-creation of the gang rape, for example, is so harrowing that one can begin to imagine her pain and thirst for rightful vengeance. To emphasize the social ramifications of Devi’s plight, Kapur contrasts her barren world, with its waterless deserts and scrub-covered hills, against the luxury of those who plotted against her. All of the political implications and the social circumstances that led to both the hatred and idolatry are rooted solidly in the film but, first and foremost, Kapur has made a rip-snorting action thriller that will please even those who don’t give a damn about India’s problems.

Phoolan Devi, by the way, was released in February 1994 by special order of the Indian Supreme Court, 12 years after her surrender. Now treated as a superstar, she plans to go into politics.

—David Overbey

Patang | The Kite

Goutam Ghose

INDIA, 1993

100 minutes Colour/35mm (Hindi)

Production Company: G.N.S. Motion Pictures Pvt. Ltd.

Producer: Durba Sahay, Sanjay Sahay

Screenplay: Goutam Ghose, Ain Rashid Khan, based on a story by Sanjay Sahay

Cinematography: Goutam Ghose

Editor: Moloy Banerjee

Art Director: Ashoke Bose

Sound: Robin Sengupta, Anup Mukherjee

Music: Goutam Ghose

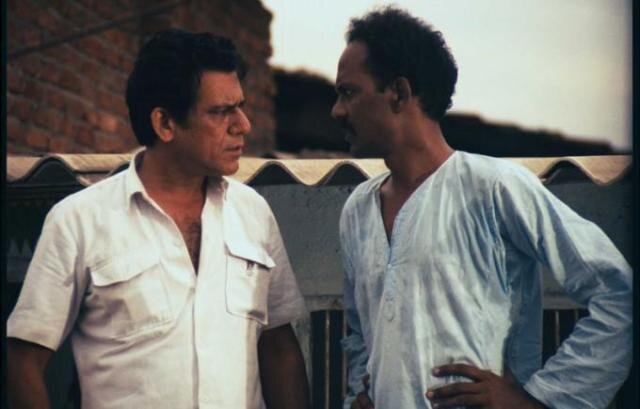

Principal Cast Shabana Azmi, Om Puri, Shatrughan Sinha, Sayed Shafique, Robi Ghosh, Mohan Aagashe, Ashad Sinha

The uniquely talented actress Shabana Azmi is the engine that drives Goutam Ghose’s impressive new film, The Kite.

Azmi is Jitni, a widow living in the dusty railway village of Manpur with her teenage son, Somra (Shatrughan Sinha of Salaam Bombay! fame). While Jitni has a scandalous affair with the local bandit (Om Puri)—his gang loots the trains as they slow down to cross a nearby bridge—her son dreams of better things as he flies his favourite kites above the heath. Then an eager, idealistic railway police inspector comes to town, just as the bandit lures Somra into his organization, and Jitni’s perilous emotional life is suddenly thrown out of kilter.

Ghose is one of India’s most visually accomplished young directors. His early career as a cinematographer and documentary-maker was notable for powerful and moving images. Last year’s Festival entry, Boatman of the River Padma, confirmed his ability with the camera and revealed a newfound talent as a more philosophically inclined storyteller. The Kite is also a departure, but for different reasons. Unafraid of commercial conventions, it seamlessly integrates strands of comedy and melodrama into its strong underlying social message.

But The Kite is finally a moving, life-affirming film about ordinary people who find themselves in extraordinary situations. It is Ghose’s ability as a filmmaker, coupled with Azmi’s warm, authoritative performance—the muse of Mrinal Sen for many years, Azmi is certainly India’s best-known actress in the West—that makes the events overtaking these people seem all the more real.

—Noah Cowan

Bollywood

Bollywood

Bikramjit “Blondie” Singh

INDIA, 1994

120 minutes Colour/35mm

Production Company: Soni-Kahn Production

Executive Producer: John Tu, David Sun, Vimal Soni

Producer: Bikramjit “Blondie” Singh

Screenplay: Bikramjit “Blondie” Singh, based on Shashi Tharoor’s novel “Show Business”

Cinematography: Jayvant Pathare

Art Director: Bikramjit “Blondie” Singh

Music: Tushar Parte

Principal Cast: Chunky Panday, Veena Bidasha, Saeed Jaffrey, Mukesh Rishi, Meera Varma, Tariq Yunus, Dipti Naval, Blondie Singh, Akash, Nilish Malhotra

Bollywood is a huge (a cast of thousands!), splashy, boisterous (30-songs), and wildly wicked satire of the biggest movie industry in the world. Its hero (anti-hero?) Ashok starts as a serious actor, but gives up Little Theatre productions of Pinter in English (and the good girl who went with them) to make it in the movies. Soon he is a huge star, turning out trash which he himself can’t remember even as he’s making it. Included, of course, are digest-versions of the many sorts of commercial Bombay talkies. This, we must remember, is India—where politics and show business are closely connected (unlike anywhere else in the world).

Ashok is the son of an honest (!) politician who encourages his son to run for office. Scandal follows. The film is chock full of characters who would be unbelievable if they weren’t drawn directly from life: the sexually voracious gossip columnist; aging stars who would kill to play one more romantic lead; the director who doesn’t know one end of a camera from the other but who’s the son of the studio head. The list is endlessly rich. It’s all great fun—fun of the malicious kind.

The film is based on “Show Business,” Shashi Tharoor’s wonderful novel, which becomes all the more powerful here because it satirizes its own medium. Bikramjit “Blondie” Singh knows all about the business: he has turned out hundreds of films from B-actioners to porn and all the small exploitation films made for a dime and sold for a dollar.

He himself says he has no truck with “intellectual cinema” and that he wants only to entertain. But that too may be part of the Bollywood game, since there are thought-provoking barbs in every one of the jokes and the impossible musical numbers.

—David Overbey

Thevar Magan

Thevar Magan

Bharathan

INDIA, 1992

145 minutes Colour/35mm (Tamil)

Production Company: Raajkamal Films International

Producer: Kamal Haasan

Screenplay: Kamal Haasan

Cinematography: P.C. Sriram

Editor: N.P. Satish

Art Director: Ashok

Music: layaraja

Choreography: Raghuram

Lyrics: Vaalee

Principal Cast: Kamal Haasan, Gowthamii, Shivaji Ganesan, Revathy Menon, Nazar, Kakaradhakrishnan, Vijai, S.N. Lakshmi, Prasanthi

Kamal Haasan is probably the biggest movie star—and one of the finest actors—in Indian cinema. At four he was a child star, and has since been in 150 films. His native language is Tamil, but he can act in Hindi, Malayalam, Telgulu, Kanada and English. He has acted in the theatre and is a well-known interpreter of Carnatic music. His stories and poems appear widely in Tamil publications and he has won every possible award in India. As well, he has insisted that his fan clubs dissolve into a social welfare organization that sets up medical camps for tribal people, among other activities.

One focuses here on Haasan because he is the source and driving force behind Thevar Magan. His screenplay for the film is difficult to summarize, since it is an absolute cornucopia of events and characters. Briefly—and inadequately—Thevar has a number of sons. The eldest is an alcoholic troublemaker who returns from his London education and immediately scandalizes the village by bringing along a girlfriend. His younger brother is not much more traditional, and marries a non-Tamil girl before starting a fast-food outlet in the city.

The rest of the film involves sacrilege, robbery, explosions, redemption, feuds, marriages and false marriages, attempted murder, religious festivals and, of course, many vibrant song-and-dance numbers. There is something for everyone in this extraordinary film. Thevar Magan is an example of Indian popular cinema at its best.

—David Overbey

English, August

English, August

Dev Benegal

INDIA, 1994

118 minutes Colour/35mm

Production Company: Tropicfilm

Producer: Dev Benegal

Screenplay: Upamanyu Chatterjee, Dev Benegal, based on Chatterjee’s novel “English, August”

Cinematography: Anoop Jotwani, Mohanan K.U.

Editor: Dev Benegal

Art Director: Anuradha Parikh-Benegal

Sound: Vikram Joglekar

Music: Vikram Joglekar, D. Wood

Principal Cast: Rahul Bose, Salim Shah, Shivaji Satham, Veerendra Saxena, Yogendra Tikku, Vivek Shah, Tanvi Azmi, Mita Vashisht, Shivraj

The subject is India—modern India, where the urban and well-to-do speak English, read English and American books, see American and French films, eschew local movies, and know more about American than Indian music. Agastya (called “English, August” for obvious reasons) Sen speaks and thinks in English. A lover of poetry, he listens to Bob Dylan, rock and jazz and reads Marcus Aurelius for pleasure. He is also an Administrative Service Officer, a member of the most influential and powerful cadre of civil servants in the country. His class, family and education indicate he will be part of modern India’s governing elite.

The very-English August is sent off for a year’s training to Madna, an obscure small town in the backwaters. Culture shock in his own country follows. He feels like a foreigner, but must survive. He spends, therefore, a lot of his time daydreaming, fantasizing and masturbating. The film, obviously, is a comedy. August is surrounded by wild characters: Srivastrava, the pompous head bureaucrat and his wife Malti, the fashion and cultural leader of the town; Sathe, a local pothead and cartoonist; Kumar, the Superintendent of Police and connoisseur of porn films; and Frogto, the world’s worst cook,

August is also surrounded by India as it is. The film was shot on location in Narsipatnam, Bhimunipatnam, and Vishakhapatnam—none on the tourist route—and Benegal has made the details of each place a major part of his fast-paced film. Like the remarkable novel on which it is based, the film is subtle, moving and profound in its observation of human foibles and understanding of disaffection with one’s own culture—particularly Indian, but far from unknown everywhere else.

—David Overbey

The Dreamer

Shilpi | The Dreamer

Nabyendu Chatterjee

INDIA, 1993

103 minutes Colour/35mm (Bengali)

Production Company: Government of West Bengal/National Film Development Corporation

Screenplay: Nabyendu Chatterjee, based on a story by Manik Bandopadhaya

Cinematography: Sakti Bandopadhaya

Editor: Nemai Roy

Art Director: Radharaman Tapadar

Sound: Anup Mukhopadhaya

Music: Nikhil Chattopadhaya

Principal Cast: Anjan Dutt, Rwita Dutta Chakraborty, Sreelekha Mukherjee, Reba Roy Chowdhury, Asit Bandopadhaya

Respected by all for his artistry, Madan is considered the genius of weaving in his village in Bengal. He counts zamindars and rich families among his clients, supplying them with beautiful and costly saris, and, once a year, for the Puja celebrations, he has the honour of weaving the apparel for Lord Viswakarma’s effigy. But during the Second World War, hoarders and black marketeers cause artificial shortages, driving up yarn prices and thus force most weavers to use second-grade goods. A whole day’s labour with this coarse yarn fails to provide one full meal a day for any family.

Madan, the idol of other artisans, refuses to work with lesser materials and the rest of the weavers follow suit. Starvation is soon widespread in the village—a fistful of rice is beyond the reach of many during the Bengal Famine—and even Madan’s family begs him to compromise, particularly since his wife is in the last stages of pregnancy. Finally, Madan manages to get one-sari’s-worth of quality yarn from a merchant who hopes to break the will of the other workers. Late in the night, the villagers are startled awake by the unexpected clatter of Madan’s loom—has the idealist fallen?—but what they discover is not what they expect.

At first glance, Nabyendu Chatterjee’s film seems to be about economic repression. It is, on one level, but the central issue concerns an artist refusing to compromise his work and soul for material gain. Weaving wonderful saris is Madan’s life. He is most alive and most at peace working at the loom. The film questions how far an artist must go to remain true to himself and still fulfil his moral obligations. In addition to the fine portrait it presents of the artist as weaver and social rebel, Chatterjee’s film is a carefully observed representation of village life and mores. Nabyendu Chaterjee here weaves a tapestry as rich as any of Madan’s magical saris.

—David Overbey

The Servile

The Servile | Vidheyan

Adoor Gopalakrishnan

INDIA, 1993

112 minutes Colour/35mm (Malayalam)

Production Company: General Pictures

Producer: K. Ravindran Nair

Screenplay: Adoor Gopalakrishnan, based on a story by Paul Zachariah

Cinematography: Ravi Varma

Editor: M. Mani

Art Director: Sivan

Sound: Devadas, Krishnaunni

Music: Vijay Bhaskar

Principal Cast: Mamootty, Golpakumar, Tanvi Azmi, Sabita Anand

The elegance, humanity and intellectual rigour of Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s work has made him one of the most revered of Indian filmmakers and a favourite of critics the world over. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, Gopalakrishnan’s films also play in front of large audiences all over his home state of Kerala, a far cry from the rest of India where “art” cinema is confined to one or two theatres in large cities. His newest film, The Servile, continues the themes implicit in The Walls, his saga of an unjustly imprisoned writer which screened at the 1990 Festival. But while The Walls posited a freedom that transcends mere physical captivity, The Servile deals with a brutal slavery that consumes mind as well as body.

Tommi is a simple migrant farmer eking out an existence with his wife on arid land. Life is hard but tolerable until Tommi is accosted in the village by Bhaskara Patelar, the degenerate and greatly feared landlord of the region. For sport, Patelar decides to terrorize Tommi: beatings, verbal humiliation and the rape of his wife, Omana, follow. While Tommi wishes to strike back, he knows the consequences of crossing such a tyrant. As the abuse continues, however, Tommi finds himself drawn to the evil man. He joins his household staff and becomes an accomplice, helping the master execute his loathsome and profane schemes. But when Patelar kills his wife and botches the cover-up, Tommi’s allegiance is severely tested.

With its thickly drawn narrative lines and characters, The Servile can serve as a grand metaphor for any modern power relationship. But the poetry of the film is perhaps found elsewhere: in Mamootty’s subtle, modulated performance as the evil Patelar; in the harsh but frequently breathtaking Karnataka landscapes; and, of course, in Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s masterful ability to distill an intriguing, accessible tale from a morally complex subject.

—Noah Cowan

Ilayum Mullum | Leaves and Thorns

K.P. Sasi

INDIA, 1993

91 minutes Colour/35mm (Malayalam)

Production Company: ALCOM (Alternate Communication Forum)

Screenplay: K.P. Sasi, P. Baburaj, Satheesh Poduval

Cinematography: Venkitaramani

Editor: K.P. Sasi

Sound: Krishna Kumar, Raj Mohan, Shammi Thilakan

Music: Ramesh Narayanan

Principal Cast: Pallavi Joshi, Santhi Krishna, Kanya, Sabanam

The subject is the repression of women. Before one reacts by rejecting yet one more film on this subject from yet one more director of the “developing world,” let it be known that this film is different. First, the tale takes place in Kerala, a region renowned for centuries as enlightened and progressive and where women have the right to education. So if this is Kerala, what is the rest of the nation like? Then, Leaves and Thorns places its characters in a clearly defined and physically wonderful environment, and makes sure we understand how the village works and what the relationships are between all the people.

Beginning with character, Sasi demonstrates how circumstances are formed by character and character, in turn, by unexamined tradition. The film focuses on four friends—Shantha, Parvathy, Sri Devi, Lakshmi—who spend their days together and work in the same weaving centre. They are also independent and dauntless, attitudes admired by some but detested by many more in the male-dominated village. Constantly harassed, the women can only turn to the ferryman Krishnan for support and can only find peace together, immersed in Kerala’s heart-stopping beauty.

Shanta drives away a suitor, enraged by her husband-to-be’s behaviour; Parvathy gets married, and her real misery begins; the town leader harasses Lakshmi on a bus and Shanta fights back. When the town acts against the friends—even their families and Krishnan desert them—there seems only one way out.

This first feature is not always perfect. Now and again, given the rage of the director, the film’s rough edges show, a fact that actually works to its advantage. There is often a naive approach to the way information is presented—a dream-dance sequence comes to mind—but it is a sweet naiveté that merges pleasingly with the quiet accomplished performances of the four leading actresses.

—David Overbey

Aadhi Haqeeqat Aadha Fasana | Children of the Silver Screen

Dilip Ghosh

INDIA, 1990

88 minutes Colour/35mm (Hindi/ English)

Production Company: National Film Development Corporation

Producer: Ravi Malik

Screenplay: Jill Misquitta

Cinematography: K.U. Mohanan

While no national cinema eschews them, child stars abound almost to excess in the Indian cinema. Dilip Ghosh tends to bypass the reasons for this and, instead, concentrates on the emotional realities behind the seemingly glamourous lives of screen children. There are those from the past, those recently grown up (many are still waiting to re-launch their careers as young adults), and those from today. Interviews of brutal frankness, concerning exploitation, broken relationships and all the horrors visited upon children are juxtaposed with clips of performances. Underlying the glamorous life are pain and folly. The film examines a major element of Indian cinema and also probes into the space between illusion and reality.

—David Overbey

The Clap Trap

Jill Misquitta

INDIA, 1993

52 minutes Colour/16mm (Hindi/ English)

Production Company: Channel 4

Executive Producer: O.P. Kohli

Producer: Sorab Irani

Cinematography: Navroze Contractor

Editor: Deepak Segal

Bollywood is famous for its vast crowd scenes and huge musical numbers, played out in literally hundreds of movies every year. The Clap Trap takes us behind the scenes, introducing us to the extras—or “junior artistes,” to use the union-mandated euphemism—who drive this cinematic engine. Eschewing voice-over narration, this engaging documentary allows the players themselves to tell their stories, often fanciful yarns as melodramatic as the films in which they appear. But there is also a bitter irony to their lives—envied by the cinema-worshipping masses, these extras are subject to slave wages and sexual exploitation. The deft hand of director Jill Misquitta—who also wrote the script for Children of the Silver Screen—unwaveringly uncovers these issues. But she never forgets the magic and levity of the Bombay movie scene, celebrating it in fabulous footage taken on sets of yet-to-be-released films.

—Noah Cowan

Father, Son and the Holy War

Anand Patwardhan

INDIA, 1994

120 minutes Colour/16mm (English/ Rajasthani/Gujarati)

Producer: Anand Patwardhan

Cinematography: Anand Patwardhan

Editor: Anand Patwardhan

Sound: Pervez Merwanji, Sanjiv Shah, Narinder Singh, Dilip Subramaniam, Simantini Dhuru, Paromita Johra

Music: Vinay Mahajan, Nav Nirman

Confrontational, disturbing and intense, Father, Son and the Holy War is a landmark documentary. Not only concerned with the communal violence which has ravaged India since Independence, director Anand Patwardhan asks what lies behind the fervour and blood. By examining, sometimes in harrowing, explosive “stolen” footage, the all-too-common signs of modern fascism—mob rules, anti-minority sloganeering, systematic destruction of property and life—he takes us to the very foundations of hate and religion.

Patwardhan spent seven years on this project, culling material from his last two long-form projects, plus material shot between and since. He is no stranger to the subject. In Memory of Friends (90), concerning Hindu/Sikh tension following Indira Gandhi’s assassination, was a film of hope; In the Name of God (92), an indictment of rising Hindu fundamentalism, was a film of anger.

Father, Son and the Holy War draws from both. “Trial By Fire,” Part One, refers to the fires—“purifying” rituals, riots, wife-burning—occupying contemporary Indian political and social consciousness. And although angry images like footage from a crematorium that permits ritual “Sati” and the charred bodies following the recent massive Bombay riots, are difficult to watch, Patwardhan balances them with his “firefighters,” people committed to end misogynist and bigoted practices within their communities.

“Hero Pharmacy,” Part Two, asks what this systemic violence stems from. Patwardhan posits an all-encompassing vision of Indian machismo, which has, as its nucleus, oft-repeated tales of marauding Hindu warriors and Mughal princes who rape and pillage with impunity. He backs up his claims by interviewing a wide range of young people and by examining the types of Western culture that have become popular in India. In this more contemplative, even philosophical mood, Anand Patwardhan diagnoses his nation’s continuing ills—and reveals a new face of fascism that chillingly parallels political movements closer to home.

—Noah Cowan

Fearless - The Hunterwali Story

Kamlabai

Reena Mohan

INDIA, 1992

46 minutes Colour/16mm (Marathi/ Hindi)

Production Company: Daguerrotype

Producer: Reena Mohan

Cinematography: Ranjan Palit

Editor: Reena Mohan, Smriti Nevatia

Sound: Suresh Rajamani

Principal Cast: Kamlabai Gokhale

Fearless—The Hunterwali Story

Riyad Vinci Wadia

INDIA, 1993

62 minutes Colour/Black and White/ 35mm (Hindi)

Production Company: Wadia Movietone Pvt. Ltd.

Producer: Riyad Vinci Wadia

Cinematography: R.M. Rao, Anil Mehta, Faroukh Mistry

Editor: Arunabha Mukherjee

Indian commercial cinema has been a star-driven affair from its inception. To this day, these larger-than-life performers are living gods to millions of movie fans across the country. The films paired here go back to the root of this love affair, profiling two very different but equally appealing actresses of the past.

Kamlabai Gokhale, now 92 years old, was one of this century’s great Marathi stage and screen actresses. Interviews with her, in tandem with beautiful period stills and judicious re-enactments, not only conjure up nostalgia for a lost cinematic past but also tell a powerful tale of a woman’s struggle against the social current of her time. Kamlabai’s legendary wit and candour are captured exquisitely by first-time director Reena Mohan.

Bold, brash and brazen, transplanted Australian Mary Evans splashed onto Indian screens in 1935’s Hunterwali, a madcap sock-‘em-up action flick that spawned a legion of imitators. Rechristened “Fearless Nadia,” the blue-eyed, blonde stunt queen became one of the era’s leading stars, cracking her whip and belting goons in the gut in dozens of quickly made features. Says she: “There was no question of a double. I’d do all the daredevilry myself. I was seldom afraid, and the thrill I derived from all this maro-pheko-todo-peeto business knew no bounds. It was all such great fun.”

Director Riyad Vinci Wadia deftly interweaves archival footage from these films with anecdotal reminiscences from the still-living legend. While the film is deliciously camp and never less than entertaining, Wadia also provides much valuable information about how and why the Bombay film scene has changed over the years.

—Noah Cowan

Shelter Of The Wings

Charachar | Shelter of the Wings

Buddhadeb Dasgupta

INDIA, 1993

83 minutes Colour/35mm (Bengali)

Production Company: Gope Movies

Executive Producer: Dulal Roy

Producer: Shankar Gope, Gita Gope

Screenplay: Buddhadeb Dasgupta, from a short story by Prafulla Roy

Cinematography: Soumendu Roy

Principal Cast: Rajit Kapoor, Laboni Sarkar, Sadhu Meher, Shankar Chakraborty, Monoj Mitra, Indrani Halder

Tragedy of an Indian Farmer

Murali Nair

INDIA, 1993

6 minutes Colour/16mm

Cinematography: Radhakrishnan

Principal Cast: MLR. Gopakumar, Stella Raja, Sashidharan Nair, Lal, Ajitha

Shelter of the Wings is a simple, gentle and affecting story with wider implications than might be evident on the surface. Lakhinder catches exotic birds in the forest of Bengal (stunningly photographed by Soumendu Roy) to sell in Calcutta markets. However, the day before he dies, his son buries a dead bird to grow a “bird blossom tree,” and Lakhinder is so affected that he cannot bear to keep the birds in cages anymore, setting free more than he sells. As his income drops, his wife complains and eventually embarks on an affair. Afraid of losing his wife, he arranges to sell his birds directly to a Calcutta dealer and thus improve his financial state. When the dealer serves him a bird for dinner, however, it is too much and he renounces his livelihood. Still unsure as to where he is headed, he tries to win his wife back. The startling and moving end of the film is impossible to describe. Dasgupta has filmed almost entirely on location, so that we are given a magical sense of place which nourishes this sensitive portrait of an eccentric of great charm.

A similar sensibility is to be found in the first short film by a young filmmaker, Murali Nair. In six minutes, Murali Nair creates the world of an Indian farmer in which we understand the reasons for his misery and the sources of his happiness without a word being spoken. Nair knows how to get maximum results with minimum resources. He also knows how to move a camera with meaning and grace. It is obvious he will be a major figure in the near future.

—David Overbey

When Hamlet Went To Mizoram

Tales from the Planet Kolkota

Ruchir Joshi

INDIA, 1993

37 minutes Colour/16mm (English/Bengali)

Production Company: Hit Films

Producer: Ruchir Joshi

Screenplay: Ruchir Joshi, Tony Cokes

Cinematography: Ranjan Palit

Editor: Reena Mohan

Sound: Suresh Rajamani

Music: D. Wood, Vikram Joglekar

When Hamlet Went to Mizoram

Pankaj Butalia

INDIA, 1990

52 minutes Colour/16mm (Mizo)

Production Company: Vital Films

Executive Producer: Pankaj Butalia

Cinematography: Ranjan Palit

Editor: Sameera Jain

Sound: Suresh Rajamani, Pankaj Butalia

The absolutely dreadful and self-serving book “City of Joy” and the yet more dreadful and self-serving film derived from it are not the first perversions of the reality of Calcutta. There have been other dreams of the city, equally false and potentially as harmful. Ruchir Joshi guides us through a gallery of images of his city, taken from Hollywood, European and Indian films, and links them to a more general exploitation that leads to further cultural and economic misery. Tales from the Planet Kolkota is a personal film, in which Joshi’s examination of illusionary Calcutta merges with memories of a friend, Deepak Majumdar, who died during production. This juxtaposition throws further light on the reality of a city of dreams and nightmares.

—David Overbey

Documentary filmmaker Pankaj Butalia’s Moksha was a sumptuous addition to last year’s Asian Horizons programme. When Hamlet Went to Mizoram, his first significant film, confirmed him earlier as an important talent.

Mizoram is a sliver of a state in the far eastern reaches of India, where people are ethnically similar to the Burmese across the border and have been engaged in a civil war with the Indian government since Independence. In his travels, Butalia discovered one town where cultural concerns and social mores, after years of war, attrition and melodramatic temperaments, congealed into reverence for one basic text: Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.”

Presumably introduced by missionaries decades ago, the play has attracted a cult that extends to best-selling audio cassettes and at least one annual theatrical production that draws vast crowds. Butalia investigates the significance of the text for these people, opening their still-closed world for us a crack. Sensitive to the ethnographic traps inherent in the project, he skirts them with a deft sense of humour and an unfailingly precise eye.

—Noah Cowan

Portrait Of A Life

Ekti Jiban | Portrait of a Life

Raja Mitra

INDIA, 1987

130 minutes Colour/35mm (Bengali)

Production Company: Chalchitra Executive

Producer: Dilip Ghosh

Screenplay: Raja Mitra, from a story by Buddhadev Basu

Cinematography: Kamal Nayek

Music: Raja Mitra

Principal Cast: Soumitra Chatterjee, Madhavi Chakrabarti, Averi Dutta, Munna Chakrabarty, Gyanesh Mukherjee

He worked for various literary and cinema magazines in Bengal. In 1974 and 1975, he was assistant director to Gautam Ghosh. Between 1975 and 1987, he made numerous short and medium-length documentaries for the cinema division of the government of West Bengal. Portrait of a Life (87) is his first feature film. Raja Mitra’s incandescent Portrait of a Life takes an almost impossible subject—the thirst for knowledge and the joy of words—and manages to make it both vital and moving. If one allows the film a quarter hour to set up its rhythm and mood, it becomes obsessively watchable, as fascinating as a good detective story.

Gurudas is a teacher of Sanskrit in a humble village school in 1930. When he suddenly realizes that Bengali has separated itself almost entirely from its Sanskrit origins and that there is no dictionary of this modern language, he sets out to create one. Taking to the streets, he searches through all walks of life for vocabulary and definitions.

Gurudas’s decades-long odyssey brings misery to his family, but it also inspires devotion and love. There is nothing flashy or easy here, but there is true humanity, true reverence for the life of the mind and the spirit. The core of the film is lit by that tiny lamp which illuminates everything worthwhile: the lamp of thought.

—David Overbey

Dharavi

Dharavi

Sudhir Mishra

INDIA, 1992

120 minutes Colour/35mm (Hindi)

Production Company: National Film Development Corporation/ Doordarshan

Producer: Ravi Malik

Screenplay: Sudhir Mishra

Cinematography: Rajesh Joshi

Editor: Renu Saluja

Art Director: Subhash Sinha Roy

Sound: Madhu Apsara, Hitendra Ghosh

Music: Rajat Dholakia

Principal Cast: Om Puri, Shabana Azmi, Raghuvir Yadav, Virendra Saxena, Pramod Bala, Madhuri Dixit

Dharavi, sprawling across the foot of Bombay, is Asia’s largest slum, a home for the thousands of migrants absorbed by the metropolis every year. Rajkaran Yadav (Om Puri) is a Dharavi taxi driver hoping for a better life. He plans to buy a factory with friends and become a rich businessman. Perhaps then he might snag the film starlet who inhabits his dreams. But Yadav’s values are questioned by his social activist brother-in-law and, in a more emotional way, by his wife (played by the incomparable Shabana Azmi, in a subtle, powerful performance). Finally, his obsession with success alienates everyone—Yadav is penniless and alone. Rejecting the stereotypical “ghetto film” for a more fanciful approach, director Sudhir Mishra uses theatrical sets and riffs on characters’ fantasies. He is ably assisted in this lyrical, performance-driven style by some of India’s finest actors: Puri and Azmi especially make the screen light up with the grace and power of their work.

—Noah Cowan

The Ferry

Kadavu | The Ferry

M.T. Vasudevan Nair

INDIA, 1991

104 minutes Colour/35mm (Malayalam)

Production Company: Novel Films

Screenplay: M.T. Vasudevan Nair, based on a story by S.K. Pottekkat

Cinematography: Venu

Editor: B. Lenin

Art Director: Bhasan

Sound: Sampath

Music: Rajiv Taranath

Principal Cast: Santhosh Antony, Balan K. Nair, Thilakan, Ravi Vallathol, Murali, Ummer

The tiny state of Kerala has consistently produced quietly masterful art films, often based on the traditions of the local Malayalam literature. The Ferry is an almost perfect example of how fruitful this collaboration can be. It follows a runaway in his late teens, who is taken on as an apprentice by a rural boatman, even though the river runs dry most of the year. Living simply with his kind mentor, the boy learns much about the village. He breaks the gentle monotony of his existence—exquisitely captured by cinematography that celebrates Kerala’s natural beauty—when a girl he likes loses her necklace. Discovering that she has moved to the city, he follows her into its noise and bustle and learns, in the process, the true nature of kindness.

The Ferry has a certain poetry to it, not so much because of the script, even though director M.T. Vasudevan Nair is a well-respected writer, but because of the subtle cinematography and skillful acting. Both manage to convey meaning through small gestures and contemplative moments.

—Noah Cowan

Marattam | Masquerade

Govindan Aravindan

INDIA, 1988

90 minutes Colour/35mm (Malayalam)

Production Company: Doordarshan India

Screenplay: Govindan Aravindan, based on the play by Kavalam Narayana Panicker Cinematography: Shaji

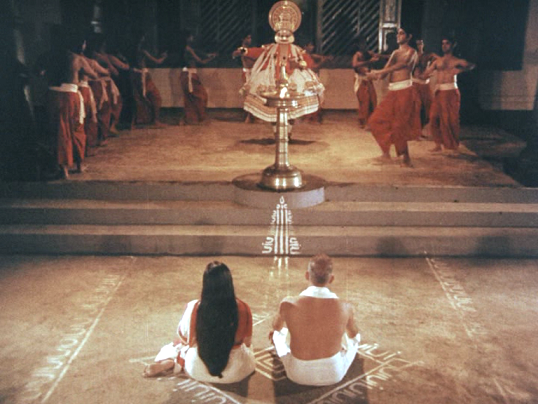

Editor: Bose

Director Aravindan, a kind, wise and witty man, inspired an entire generation of filmmakers because he ignored commercialism and current trends, producing a totally personal and independent form of cinema. Masquerade, one of his best films, is both a remembrance of and an homage to the man and the director. Aravindan made his films from what interested him: Indian art, music and social problems. As an accomplished musician, he was fascinated by music and dance, particularly when combined with poetry. Masquerade, which uses the last sequences of a Kathakali play, tells the story—in dance and music—of a murder. Using narrative poetry, three different versions of the killing are enacted, the episodes set to the rhythm of three different styles of traditional folk singing. Masquerade is based on the concept of transformation of an actor into acharacter and the basic concept of maya, or illusion. Those who like dance films will be stunned by Masquerade’s originality and energy; those who generally don’t may well discover that they are intrigued and excitingly entertained.

—David Overbey

Baazigar

Abbas-Mustan

INDIA, 1993

90 minutes Colour/35mm (Hindi)

Production Company: United Seven

Producer: Ganesh Jain

Screenplay: Robin Bhatt, Javed Sidique, Akash Khurana

Cinematography: Thomas A, Xavier

Editor: Hussain A. Burmawala

Art Director: R. Verman

Sound: Narendra Shinde

Music: Anu Malik

Sound: Devadas

Principal Cast: Urmila Unni, Sadanam Krishnan Kutty, Kalamandalam Kesavan, The Thiruvarangu Ensemble

Part violent thriller, part romantic comedy and full of great songs, Baazigar stands head-and-shoulders above most recent Bombay Masala movies. This mega-box-office success established handsome, boyish Shah Rukh Khan as India’s biggest star in a role that spawned an entirely new genre: the anti-hero musical.

Loosely based on A Kiss Before Dying, Baazigar divides neatly into two halves. Part one sees two sisters, Seema and Priya, strike up a secret romance with the same man (Khan). Sweet sentimental moments are punctuated by over-the-top dance numbers, but then tragedy strikes and Seema lies dead. Part two is the manhunt and the mystery that follows, ending in fierce melodrama and an exquisitely choreographed bloody showdown.

Co-directors Abbas and Mustan manage to wring every nuance out of their talented stars, and show they can handle any genre with ease. The music—a traditional film score, plus Brazilian and flamenco rhythms—is also an absolute delight. If you have never seen a proper Masala, Baazigar is an excellent place to start.

—Noah Cowan